NEW YORK (AP) — The White House blocked an Associated Press reporter from an event in the Oval Office on Tuesday after demanding the news agency alter its style on the Gulf of Mexico, which President Donald Trump has ordered renamed the Gulf of America.

The reporter, whom the AP would not identify, tried to enter the White House event as usual Tuesday afternoon and was turned away. Later, a second AP reporter was barred from a late-evening event in the White House's Diplomatic Reception Room.

The highly unusual ban, which Trump administration officials had threatened earlier Tuesday unless the AP changed the style on the Gulf, could have constitutional free-speech implications.

Julie Pace, AP's senior vice president and executive editor, called the administration's move unacceptable.

“It is alarming that the Trump administration would punish AP for its independent journalism,” Pace said in a statement. “Limiting our access to the Oval Office based on the content of AP’s speech not only severely impedes the public’s access to independent news, it plainly violates the First Amendment.”

The Trump administration made no immediate announcements about the moves, and there was no indication any other journalists were affected. Trump has long had an adversarial relationship with the media. On Friday, the administration ejected a second group of news organizations from Pentagon office space.

Before his Jan. 20 inauguration, Trump announced plans to change the Gulf of Mexico’s name to the “Gulf of America” — and signed an executive order to do so as soon as he was in office. Mexico’s president responded sarcastically and others noted that the name change would probably not affect global usage.

Besides the United States, the body of water — named the Gulf of Mexico for more than 400 years — also borders Mexico.

The AP said last month, three days after Trump’s inauguration, that it would continue to refer to the Gulf of Mexico while noting Trump’s decision to rename it as well. As a global news agency that disseminates news around the world, the AP says it must ensure that place names and geography are easily recognizable to all audiences.

AP style is not only used by the agency. The AP Stylebook is relied on by thousands of journalists and other writers globally.

Barring the AP reporter was an affront to the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which bars the government from impeding the freedom of the press, said Tim Richardson, program director of journalism and misinformation for PEN America.

The White House Correspondents Association called the White House move unacceptable and called on the administration to change course.

“The White House cannot dictate how news organizations report the news, nor should it penalize working journalists because it is unhappy with their editors' decision,” said Eugene Daniels, WHCA's president.

This week, Google Maps began using “Gulf of America," saying it had a “longstanding practice” of following the U.S. government’s lead on such matters. The other leading online map provider, Apple Maps, was still using “Gulf of Mexico" earlier Tuesday but by early evening had changed to “Gulf of America" on some browsers, though at least one search produced results for both.

Trump also decreed that the mountain in Alaska known as Mount McKinley and then by its Indigenous name, Denali, be shifted back to commemorating the 25th president. President Barack Obama had ordered it renamed Denali in 2015. AP said last month it will use the official name change to Mount McKinley because the area lies solely in the United States and Trump has the authority to change federal geographical names within the country.

David Bauder writes about the intersection of media and entertainment for the AP. Follow him at http://x.com/dbauder and https://bsky.app/profile/dbauder.bsky.social

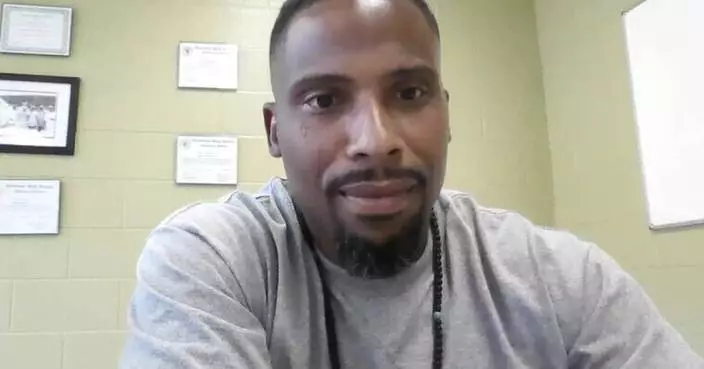

Elon Musk listens as President Donald Trump speaks with reporters in the Oval Office at the White House, Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2025, in Washington. (Photo/Alex Brandon)

DEIR AL-BALAH, Gaza Strip (AP) — Israel launched airstrikes across the Gaza Strip early Tuesday, killing more than 400 Palestinians, local health officials said, and shattering a ceasefire in place since January with its deadliest bombardment in a 17-month war with Hamas.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu ordered the strikes, which killed mostly women and children, after Hamas refused Israeli demands to change the ceasefire agreement. Officials said the operation was open-ended and expected to expand. The White House said it had been consulted and voiced support for Israel’s actions.

The Israeli military ordered people to evacuate eastern Gaza and head toward the center of the territory, indicating that Israel could soon launch renewed ground operations. The new campaign comes as aid groups warn supplies are running out two weeks after Israel cut off all food, medicine, fuel and other goods to Gaza’s 2 million Palestinians.

“Israel will, from now on, act against Hamas with increasing military strength,” Netanyahu’s office said.

The attack during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan could signal the full resumption of a war that has already killed tens of thousands of Palestinians and caused widespread destruction across Gaza. It also raised concerns about the fate of the roughly two dozen hostages held by Hamas who are believed to still be alive.

The renewal of the campaign against Hamas, which receives support from Iran, came as the U.S. and Israel stepped up attacks this week across the region. The U.S. launched deadly strikes against Iran-allied rebels in Yemen, while Israel has targeted Iran-backed militants in Lebanon and Syria.

A senior Hamas official said Netanyahu’s decision to return to war amounts to a “death sentence” for the remaining hostages. Izzat al-Risheq accused Netanyahu of launching the strikes to save his far-right governing coalition.

Hamas said at least six senior officials were killed in Tuesday’s strikes. Israel said they included the head of Hamas' civilian government, its justice minister and two security agency chiefs. There were no reports of any attacks by Hamas several hours after the bombardment.

But Yemen's Houthi rebels fired rockets toward Israel for the first time since the ceasefire began. The volley set off sirens in Israel's southern Negev desert but was intercepted before it reached the country's territory, the military said.

The strikes came as Netanyahu faces mounting domestic pressure, with mass protests planned over his handling of the hostage crisis and his decision to fire the head of Israel’s internal security agency. His latest testimony in a long-running corruption trial was canceled after the strikes.

The strikes appeared to give Netanyahu a political boost. A far-right party led by Itamar Ben-Gvir that had bolted the government over the ceasefire announced Tuesday it was rejoining.

The main group representing families of the hostages accused the government of backing out of the ceasefire. “We are shocked, angry and terrified by the deliberate dismantling of the process to return our loved ones from the terrible captivity of Hamas,” the Hostages and Missing Families Forum said.

Strikes across Gaza pounded homes, sparked fires in a tent camp outside the southern city of Khan Younis and hit at least one school-turned-shelter.

After two months of relative calm during the ceasefire, stunned Palestinians found themselves once again digging loved ones out of rubble and holding funeral prayers over the dead at hospital morgues.

“Nobody wants to fight,” Nidal Alzaanin, a resident of Gaza City, said. “Everyone is still suffering from the previous months.”

A hit on a home in Rafah killed 17 members of one family, according to the European Hospital, which received the bodies. The dead included five children, their parents, and another father and his three children. Another in Gaza City killed 27 members of a family, half of them women and children, including a 1-year-old, according to a list of the dead put out by Palestinian medics.

At Khan Younis’s Nasser Hospital, patients lay on the floor, some screaming. A young girl cried as her bloody arm was bandaged. Wounded children overwhelmed the pediatric ward, said Dr Tanya Haj-Hassan, a volunteer with Medical Aid for Palestinians aid group.

She said she helped treat a 6-year-old girl with internal bleeding. When they pulled away her curly hair, they realized shrapnel had also penetrated the left side of her brain, leaving her paralyzed on the right side. She was brought in with no ID, and “we don't know if her family survived,” Haj-Hassan said.

Gaza’s Health Ministry said the strikes killed at least 404 people and wounded more than 560. Zaher al-Waheidi, head of the ministry’s records department, said at least 263 of those killed were women or children under 18. He described it as the deadliest day in Gaza since the start of the war.

The war has killed over 48,500 Palestinians, according to local health officials, and displaced 90% of Gaza’s population. The Health Ministry doesn’t differentiate between civilians and militants but says over half of the dead have been women and children.

The war erupted when Hamas-led militants stormed into southern Israel on Oct 7, 2023, killing some 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and taking 251 hostages. Most have been released in ceasefires or other deals, with Israeli forces rescuing only eight and recovering dozens of bodies.

The White House blamed Hamas for the renewed fighting. National Security Council spokesman Brian Hughes said the militant group “could have released hostages to extend the ceasefire but instead chose refusal and war.”

The ceasefire deal that the U.S. helped broker, however, did not require Hamas to release more hostages to extend the halt in fighting beyond its first phase.

An Israeli official, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss the unfolding operation, said Israel was striking Hamas’ military, leaders and infrastructure and planned to expand the operation beyond air attacks.

The official accused Hamas of attempting to rebuild and plan new attacks. Hamas militants and security forces quickly returned to the streets in recent weeks after the ceasefire went into effect. Hamas on Tuesday denied planning new attacks.

Under the ceasefire that began in mid-January, Hamas released 25 hostages and the bodies of eight more in exchange for more than 1,700 Palestinian prisoners as agreed in the first phase.

But Israel balked at entering negotiations over a second phase. Under the agreement, phase two was meant to bring the freeing of the remaining 24 living hostages, an end to the war and full Israeli withdrawal from Gaza. Israel says Hamas also holds the remains of 35 captives.

Instead, Israel demanded Hamas release half of the remaining hostages in return for a ceasefire extension and a vague promise to eventually negotiate a lasting truce. Hamas refused, demanding the two sides follow the original deal, which called for the halt in fighting to continue during negotiations over the second phase.

The deal had largely held, though Israeli forces have killed dozens of Palestinians who the military says approached its troops or entered unauthorized areas. Egypt, Qatar and the United States have been trying to mediate the next steps.

Israel says it will not end the war until it destroys Hamas’ governing and military capabilities and frees all hostages — two goals that could be incompatible.

A full resumption of the war would allow Netanyahu to avoid the tough trade-offs called for in the second phase and the thorny question of who would govern Gaza.

It would also shore up his coalition, which depends on far-right lawmakers who want to depopulate Gaza and rebuild Jewish settlements there.

Released hostages have repeatedly implored the government to press ahead with the ceasefire to return all remaining captives. Tens of thousands of Israelis have joined protests calling for a ceasefire and return of all hostages.

Federman reported from Jerusalem and Magdy from Cairo. Associated Press reporters Mohammad Jahjouh in Khan Younis, Gaza Strip; Abdel Kareem Hana in Gaza City, Gaza Strip; Fatma Khaled in Cairo; and Tia Goldenberg in Tel Aviv, Israel, contributed.

Follow AP’s war coverage at https://apnews.com/hub/israel-hamas-war

Protesters demand the release of hostages held in the Gaza Strip, in Tel Aviv, Israel, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariel Schalit)

Protesters demand the release of hostages held in the Gaza Strip, in Tel Aviv, Israel, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariel Schalit)

An explosion erupts in the northern Gaza Strip, as seee from southern Israel, on Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Leo Correa)

A man mourns over the body of a child, lying among other victims at the hospital morgue, following Israeli airstrikes in Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Mohammad Jahjouh)

EDS NOTE GRAPHIC CONTENT.- A woman mourns over the body of a person killed in overnight Israeli army airstrikes across the Gaza Strip, at the Al-Ahli hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

A woman mourns as she identifies a body in the Al-Ahli hospital following overnight Israeli airstrikes across the Gaza Strip, in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

A woman reacts as she stands over the bodies of people killed during overnight Israeli army airstrikes across the Gaza Strip, at the Al-Ahli hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

A woman carries the body of a child to Al-Ahli hospital following overnight Israeli airstrikes across the Gaza Strip, in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

A woman reacts over the body of a person killed during overnight Israeli army airstrikes across the Gaza Strip, at the Al-Ahli hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

A woman reacts next to bodies of Palestinians who were killed in an Israeli army airstrikes are brought to the Al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

Mourners gather around the bodies of Palestinians who were killed in an Israeli army airstrikes as they are brought to Al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

Mourners gather around the bodies of Palestinians who were killed in an Israeli army airstrikes as they are brought to Al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

Palestinians inspect the damage at Al-Tabi'in School in central Gaza Strip following an Israeli airstrike, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

Palestinians inspect the damage at Al-Tabi'in School in central Gaza Strip following an Israeli airstrike, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

A man carries a covered body following overnight Israeli airstrikes across the Gaza Strip, at the Al-Ahli hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

EDS NOTE GRAPHIC CONTENT.- A man carries the body of a child to the Al-Ahli hospital following multiple overnight Israeli airstrikes across the Gaza Strip, in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

Bodies of people killed during overnight Israeli army airstrikes across the Gaza Strip are left in the yard of the the Al-Ahli hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

Palestinians inspect the damage at Al-Tabi'in School in central Gaza Strip following an Israeli airstrike, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

Palestinians inspect the damage at Al-Tabi'in School in central Gaza Strip following an Israeli airstrike, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)

People gather around the bodies of Palestinians who were killed in an Israeli army airstrikes as they are brought to the Al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

A Palestinian man holds the body of his 11 month-old nephew Mohammad Shaban, killed in an Israeli army airstrikes at the Al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

The bodies of Palestinians killed in Israeli army airstrikes are brought to Shifa hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

Injured Palestinians wait for treatment at the hospital following Israeli army airstrikes in Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Mohammad Jahjouh)

The bodies of Palestinians killed in an Israeli army airstrikes are brought to Shifa hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

A body of a Palestinian killed in an Israeli army airstrikes is brought to Shifa Hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

The bodies of Palestinians killed in an Israeli army airstrikes are brought to Shifa hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

Palestinians mourn their relative who was killed in an Israeli army airstrikes, at Shifa Hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

The bodies of Palestinians killed in an Israeli army airstrikes are brought to Shifa hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

The bodies of Palestinians killed in an Israeli army airstrikes are brought to Shifa hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

The bodies of Palestinians killed in an Israeli army airstrikes are brought to Shifa hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

EDS NOTE: GRAPHIC CONTENT - EDS NOTE GRAPHIC CONTENT.- Palestinians hold the hands of their relative who was killed in an Israeli army airstrike, at Shifa Hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Karem Hanna)

A body of a Palestinian killed in an Israeli army airstrikes is brought to Shifa Hospital in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

An injured man waits for treatment on the floor of a hospital following Israeli airstrikes in Khan Younis, in the southern Gaza Strip, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Mohammad Jahjouh)

Injured Palestinians wait for treatment at the hospital following Israeli army airstrikes in Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Mohammad Jahjouh)

A man mourns over the body of a child, lying among other victims at the hospital morgue, following Israeli airstrikes in Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Mohammad Jahjouh)

A man mourns as he places the body of a child in the hospital morgue following Israeli army airstrikes in Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, on Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Mohammad Jahjouh)

An ambulance carrying victims of an Israeli army strike arrives at the hospital in Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, Tuesday March 18, 2025.(AP Photo/ Mohammad Jahjouh)

A dead person killed during an Israeli army strike is taken into the hospital in Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, Tuesday March 18, 2025.(AP Photo/ Mohammad Jahjouh)

A dead person killed during an Israeli army strike is taken into the hospital in Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, Tuesday March 18, 2025.(AP Photo/ Mohammad Jahjouh)