PHILADELPHIA (AP) — On a frigid February morning, Vanity Cordero, a Philadelphia police officer, heard a call over the radio for a man threatening to jump from a bridge. The details sounded familiar.

When Cordero arrived, she realized she’d met him months earlier on the same bridge, where she talked him down by engaging him in conversation about his family and by bringing him a hot meal.

Click to Gallery

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) members Therapist Krystian Gardner, left, and Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero talk after a call in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) member Therapist Krystian Gardner speaks during an interview in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) members Therapist Krystian Gardner, left, and Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero prepare to go out on calls in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) members Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero, left, and Therapist Krystian Gardner check a computer for calls to assist on in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) member Therapist Krystian Gardner speaks with her partner Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) member Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero walks back to her vehicle after checking on a person, Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) member Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero checks for a computer for possible calls to assist on in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) members Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero checks a computer for calls to assist on, in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) members Therapist Krystian Gardner, right, and Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero talk after convincing a person to go into hospital for mental health treatment in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) members Therapist Krystian Gardner, right, and Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero move to their vehicle near the start of their shift in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Cordero is a member of a program that pairs trained officers with mental health and social work clinicians to respond to 911 calls and other crises. It's focused on de-escalation practices and providing connections to services including follow-up support as an alternative to arrest and entering into the criminal justice system.

The unit started as a pilot program in late 2022, nearly two years after the fatal police shooting of Walter Wallace Jr., who was experiencing a mental health episode when police responded to his mother's call for help.

Studies over the past two decades have shown a person with serious mental illness can be over 10 times more likely to experience use of force during police interactions.

In the wake of Wallace's death, the police and the city both invested in programs to better respond to mental health crises — one of dozens of similar initiatives in other police departments across the country.

What makes Philadelphia's unit unique is the robust follow-up resources and that most of the officers on Philadelphia's team, including Cordero, have personal experiences that made them want to join — family members with mental illness or addictions or previous work with at-risk populations.

Cordero grew up living with her uncle, who her mother takes care of because of an intellectual disability that today would be diagnosed as autism, she said. She's an advocate for better practices for police interacting with autistic people.

“When I’m on the street and I’m serving in the community, I think of someone being my uncle or, you know, any family member. Everyone is a family member to someone,” she said. ”It just gives you a little bit more edge and patience and courteousness to the people that need your help."

On this February morning, Cordero rushed to the bridge as a member of the Crisis Intervention Response Team to help responding patrol officers.

CIRT teams, who drive SUVs without police lights and department decals and wear less formal uniforms, are often requested by other officers to assist, and also choose calls to respond to citywide.

She stayed back until she was needed, but the man spotted her and teased her about not being as tan as she was the last time they saw each other.

They laughed about Cordero getting pale over the winter months and she reminded him it was cold outside, especially on that bridge.

A few hours later, the man was on his way to a mandatory mental health hold and clinician Krystian Gardner would follow up in the coming days and offer resources to the man's family.

A lot of officers on the team said many calls were about mental health when they were on regular patrol. But officers usually have just a few minutes to spend handling calls before being pulled to the next incident.

The CIRT team, however, spends more than an hour on average with each person, said Lt. Victoria Casale, who oversees the unit.

“In policing, there just isn't the resources or time to spend hours on calls,” Casale said. “But we want our officers to spend time with people. We're not leaving you. We're trying to solve this problem with you.”

The team's clinicians, who work for the nonprofit Merakey, a behavioral health provider, also bring experience and resources to the table.

Audrey Lundy, program director for Merakey, said one of her first calls with the unit reframed her perspective. Instead of doing a typical welfare check — on a mother who hadn't been to work in awhile — Lundy and the CIRT officer brought over groceries for the family using a flexible needs spending card. The woman had gotten sick, was unable to work and began experiencing a financial crisis.

The groceries opened the door to a broader conversation about the resources that may be available to help her cover school costs, long-term expenses and ultimately, get back to her job.

The officers like the idea of being problem solvers. For Officer Kenneth Harper, a Marine combat veteran, his CIRT assignment has given him the opportunity to help fellow veterans having a hard time readjusting to civilian life or dealing with mental health concerns.

“There was a gentleman that served over 30 years in the Army — a very decorated, highly respected person,” Harper said. “But he was very stubborn, never received any help or services.”

Harper and another officer with military experience built a rapport with the man, eventually getting him to the veterans hospital for treatment and help with housing.

“We kept in touch for months after that, checking in,” he said.

Casale said Harper has gone far above and beyond, even recruiting other veterans in the department to share trainings about trauma responses and resources for vets.

It's just one way the small unit has expanded its reach. The eight-officer CIRT team covers the entire city on weekdays, but crises don't stop on nights and weekends. Casale hopes the team can grow in numbers as districts across the city become familiar with and trust the work they do.

They want people to call CIRT directly if they need help instead of waiting until it's an emergency and calling 911.

“We want them to call us,” Cordero said, of connecting with the man on the bridge. “I told him, you know, you can call us. We can just go eat. We don’t have to keep meeting on this bridge.”

This story includes discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the U.S. is available by calling or texting 988. There is also an online chat at 988lifeline.org.

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) members Therapist Krystian Gardner, left, and Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero talk after a call in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) member Therapist Krystian Gardner speaks during an interview in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) members Therapist Krystian Gardner, left, and Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero prepare to go out on calls in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) members Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero, left, and Therapist Krystian Gardner check a computer for calls to assist on in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) member Therapist Krystian Gardner speaks with her partner Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) member Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero walks back to her vehicle after checking on a person, Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) member Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero checks for a computer for possible calls to assist on in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) members Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero checks a computer for calls to assist on, in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) members Therapist Krystian Gardner, right, and Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero talk after convincing a person to go into hospital for mental health treatment in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Crisis Intervention Response Team (CIRT) members Therapist Krystian Gardner, right, and Philadelphia Police Officer Vanity Cordero move to their vehicle near the start of their shift in Philadelphia, Friday, March 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

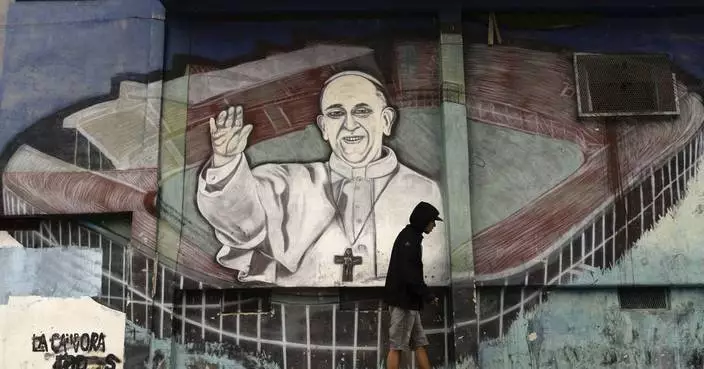

BAGHDAD (AP) — The death of Pope Francis has sent shockwaves through Iraq’s Christian community, where his presence once brought hope after one of the darkest chapters in the country’s recent history.

His 2021 visit to Iraq, the first ever by a pope, came after years of conflict and displacement. Just a few years before that, many Iraqi Christians had fled their homes as Islamic State militants swept across the country.

Christian communities in Iraq, once numbering over a million, had already been reduced to a fraction of their former number by decades of conflict and mass emigration.

In Mosul, the site of some of the fiercest battles between Iraqi security forces and the Islamic State, Chaldean Archbishop Najeeb Moussa Michaeel recalled the pope’s visit to the battle-scarred city at a time when many visitors were still afraid to come as a moment of joy, “like a wedding for the people of Mosul."

“He broke this barrier and stood firm in the devastated city of Mosul, proclaiming a message of love, brotherhood, and peaceful coexistence,” Michaeel said.

As Francis delivered a speech in the city’s al-Midan area, which had been almost completely reduced to rubble, the archbishop said, he saw tears falling from the pope’s eyes.

Sa’dullah Rassam, who was among the Christians who fled from Mosul in 2014 in the face of the IS offensive, was also crying as he watched the pope leave the church in Midan that day.

Rassam had spent years displaced in Irbil, the seat of northern Iraq's semiautonomous Kurdish region, but was among the first Christians to return to Mosul, where he lives in a small house next to the church that Francis had visited.

As the pope's convoy was leaving the church, Rassam stood outside watching, tears streaming down his face. Suddenly the car stopped, and Francis got out to greet him.

“It was the best day of my life,” Rassam said. The pope's visit “made us feel loved and heard, and it helped heal our wounds after everything that happened here," he said.

The visit also helped to spur a drive to rebuild the city’s destroyed sites, including both Muslim and Christian places of worship.

“After the wide international media coverage of his visit, many parties began to invest again in the city. Today, Mosul is beginning to rise again,” Michaeel said. “You can see our heritage reappear in the sculptures, the churches and the streets.”

Chaldean Patriarch Cardinal Louis Raphael Sako told The Associated Press that Francis had built strong relationships with the Eastern rite churches — which are often forgotten by their Latin rite counterparts — and with Muslim communities.

The patriarch recalled urging Francis early in his papacy to highlight the importance of Muslim-Christian coexistence.

After the pope’s inaugural speech, in which he thanked representatives of the Jewish community for their presence, Sako said, “I asked him, ‘Why didn’t you mention Muslims?’... He said, ‘Tomorrow I will speak about Muslims,’ and indeed he did issue a statement the next day."

Francis went on to take “concrete steps to strengthen relationships” between Christians and Muslims through visits to Muslim-majority countries — including Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Jordan as well as Iraq — Sako said. “He brought Muslims and Christians together around shared values.”

His three-day visit to Iraq “changed Iraq’s face — it opened Iraq to the outside world,” Sako said, while “the people loved him for his simplicity and sincerity.”

The patriarch said that three months before the pope’s death, he had given him a gift of dates from Iraq, and Francis responded that he “would never forget Iraq and that it was in his heart and in his prayers.”

During his visit to Iraq, Francis held a historic meeting with the country's top Shiite cleric, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, at the latter’s home in Najaf.

Sistani’s office in a statement Monday expressed “deep sorrow” at the pope’s death, saying he was “greatly respected by all for his distinguished role in serving the causes of peace and tolerance, and for expressing solidarity with the oppressed and persecuted across the globe.”

The meeting between the two religious leaders had helped to “promote a culture of peaceful coexistence, reject violence and hatred, and uphold values of harmony based on safeguarding rights and mutual respect among followers of different religions and intellectual traditions,” it said.

In Irbil, Marvel Rassam recalled joining the crowds who packed into a stadium to catch a glimpse of the pope.

The visit brought a sense of unity, Rassam said, “as everyone attended to see him, and not only the Catholics.”

“He was our favorite pope, not only because he was the first to visit Iraq, but he was also very special and unique for his humility and inclusivity,” he said.

At St. Joseph Chaldean Cathedral in Baghdad, where Francis led a Mass during his 2021 visit, church pastor Nadhir Dako said the pope's visit had carried special weight because it came at a time when Christians in Iraq were still processing the trauma of the IS attacks.

“We, the Christians, were in very difficult situation. There was frustration due to the forcible migration and the killing that occurred," Dako said. "The visit by the pope created a sort of determination for all Iraqis to support their Christian brothers.”

——-

Martany reported from Irbil, Iraq.

FILE.- Pope Francis arrives at a meeting with the Qaraqosh community at the Church of the Immaculate Conception, in Qaraqosh, Iraq, Sunday, March 7, 2021. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini,File)

FILE.- Women wait outside the Chaldean Cathedral of Saint Joseph, in Baghdad, Iraq, Saturday, March 6, 2021, where Pope Francis, depicted on a giant poster at their back, is concelebrating a mass. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini,File)

FILE - Pope Francis is welcomed as he arrives at Irbil airport, Iraq, March 7, 2021. (AP Photo/Hadi Mizban, file)

FILE.- Iraqi security forces deploy in Mosul, northern Iraq, once the de-facto capital of IS, where Pope Francis will pray for the victims of war at Hosh al-Bieaa Church Square, Sunday, March 7, 2021. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini,File)

FILE.- Pope Francis stands with religious leaders during an interreligious meeting near the archaeological area of the Sumerian city-state of Ur, 20 kilometers south-west of Nasiriyah, Iraq, Saturday, March 6, 2021.(AP Photo/Andrew Medichini,File)

FILE.- Pope Francis waves as he arrives for an open air Mass at a stadium in Irbil, Iraq, Sunday, March 7, 2021. (AP Photo/Hadi Mizban,File)

FILE - Pope Francis waves as he arrives for an open air Mass at a stadium in Irbil, Iraq, March 7, 2021. (AP Photo/Hadi Mizban, file)

Louis Sako, patriarch of Iraq's Chaldean Catholic Church, speaks during an interview with The Associated Press in Baghdad, Iraq, Monday, April 21, 2025. (AP Photo/Hadi Mizban)

FILE.- Iraqi Christians say goodbye to Pope Francis after an open air Mass at a stadium in Irbil, Iraq, Sunday, March 7, 2021. (AP Photo/Hadi Mizban,File)

FILE.- Pope Francis, surrounded by shells of destroyed churches, listens to Mosul and Aqra Archbishop Najib Mikhael Moussa during a gathering to pray for the victims of war at Hosh al-Bieaa Church Square, in Mosul, Iraq, once the de-facto capital of IS, Sunday, March 7, 2021.(AP Photo/Andrew Medichini,FIle)