It wasn't just a salute to a president, it was a tribute to a generation.

President George H. W. Bush was remembered during more than two days of ceremonies and services in Washington as the last president forged from World War II, a leader dedicated to military service, bipartisanship, responsibility and hard choices.

"Dad taught us that public service is noble and necessary, that one can serve with integrity and hold true to the important values like faith and family," former President George W. Bush said of his father at the funeral on Wednesday.

Former President Jimmy Carter, and Rosalynn Carter hold hands as they walk from a State Funeral for former President George H.W. Bush at the National Cathedral, Wednesday, Dec. 5, 2018, in Washington. (AP PhotoCarolyn Kaster)

"When he lost, he shouldered the blame," Bush added.

Bush spoke to an audience only sprinkled with other members of what's been called "the greatest generation." There are few left among Washington's elite. Congress said goodbye to its last World War II veterans in 2015. In the audience was former Sen. Bob Dole, 95, a veteran of the same war, who on Tuesday rose from his wheelchair with assistance to salute Bush's casket under the Capitol Rotunda. President Jimmy Carter, 94, who spent the war years at the Naval Academy, attended with his wife, Rosalynn.

"George Herbert Walker Bush was America's last great soldier-statesman, a 20th century founding father," historian Jon Meacham told the invitation-only crowd at Washington National Cathedral. "He governed with virtues that most closely resemble those of ... men who believed in causes larger than themselves."

Former Sen. Bob Dole salutes the flag-draped casket containing the remains of former President George H.W. Bush as he lies in state at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, Dec. 4, 2018. (AP PhotoManuel Balce Ceneta)

Implicit in messages was the notion that some of those values are slipping from public life.

Listening in the front row were former Presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton and President Donald Trump, none of whom fought in the wars of their time. Neither Clinton, Obama nor Trump served in the military.

Added former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney: "I believe it will be said that no occupant of the Oval Office was more courageous, more principled and more honorable than George Herbert Walker Bush."

Former Wyoming Sen. Alan Simpson, 87, described Bush as "one of nature's noblemen."

"He often said: 'When the really tough choices come, it's the country, not me. Not about Democrats or Republicans, it's for our country that I fought for.''"

Follow Kellman on Twitter at http://www.twitter.com/APLaurieKellman

DORAL, Fla. (AP) — Wilmer Escaray left Venezuela in 2007 and enrolled at Miami Dade College, opening his first restaurant six years later.

Today he has a dozen businesses that hire Venezuelan migrants like he once was, workers who are now terrified by what could be the end of their legal shield from deportation.

Since the start of February the Trump administration has ended two federal programs that together allowed more 700,000 Venezuelans to live and work legally in the U.S. along with hundreds of thousands of Cubans, Haitians and Nicaraguans.

In the largest Venezuelan community in the United States, people dread what could face them if lawsuits that aim to stop the government fail. It's all anyone discusses in “Little Venezuela” or “Doralzuela,” a city of 80,000 people surrounded by Miami sprawl, freeways and the Florida Everglades.

People who lose their protections would have to remain illegally at the risk of being deported or return home, an unlikely route given the political and economic turmoil in Venezuela.

“It’s really quite unfortunate to lose that human capital because there are people who do work here that other people won’t do,” Escaray, 37, said at one of his “Sabor Venezolano” restaurants.

Spanish is more common than English in shopping centers along Doral's wide avenues, and Venezuelans feel like they're back home but with more security and comfort.

A sweet scent wafts from round, flat cornmeal arepas sold at many establishments. Stores at gas stations sell flour and white cheese used to make arepas and T-shirts and hats with the yellow, blue and red stripes of the Venezuelan flag.

John came from Venezuela nine years ago and bought a growing construction company with a partner. He and his wife are on Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, which Congress created in 1990 for people in the United States whose homelands are considered unsafe to return due to natural disaster or civil strife. Beneficiaries can live and work while it lasts but TPS carries no path to citizenship.

Born in the U.S., their 5-year-old daughter is a citizen. John, 37, asked to be identified by first name only for fear of being deported.

His wife helps with administration at their construction business while working as a real-estate broker. The couple told their daughter that they may have to leave the United States. Venezuela is not an option.

“It hurts us that the government is turning its back on us,” John said. “We aren’t people who came to commit crimes; we came to work, to build.”

A federal judge ordered on March 31 that temporary protected statuswould stand until a legal challenge's next stage in court and at least 350,000 Venezuelans were temporarily spared becoming illegal. Escaray, the owner of the restaurants, said nearly all of his 150 employees are Venezuelan and more than 100 are on TPS.

The federal immigration program that allowed more than 500,000 Cubans, Venezuelans, Haitians and Nicaraguans to work and live legally in the U.S. — humanitarian parole — expires April 24 absent court intervention.

Venezuelans were one of the main beneficiaries when former President Joe Biden sharply expanded TPS and other temporary protections. Trump tried to end them in his first term and now his second.

The end of the temporary protections has generated little political reaction among Republicans except for three Cuban-American representatives from Florida who called for avoiding the deportations of affected Venezuelans. Mario Díaz Ballart, Carlos Gimenez and Maria Elvira Salazar have urged the government to spare Venezuelans without criminal records from deportation and review TPS beneficiaries on a case-by-case basis.

The mayor of Doral, home to a Trump golf club since 2012, wrote a letter to the president asking him to find a legal pathway for Venezuelans who haven’t committed crimes.

“These families do not want handouts,” said Christi Fraga, a daughter of Cuban exiles. “They want an opportunity to continue working, building, and investing in the United States.”

About 8 million people have fled Venezuela since 2014, settling first in neighboring countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. After the COVID-19 pandemic, they increasingly set their sights on the United States, walking through the notorious jungle in Colombia and Panama or flying to the United States on humanitarian parole with a financial sponsor.

In Doral, upper-middle-class professionals and entrepreneurs came to invest in property and businesses when socialist Hugo Chávez won the presidency in the late 1990s. They were followed by political opponents and entrepreneurs who set up small businesses. In recent years, more lower-income Venezuelans have come for work in service industries.

They are doctors, lawyers, beauticians, construction workers and house cleaners. Some are naturalized U.S. citizens or live in the country illegally with U.S.-born children. Others overstay tourist visas, seek asylum or have some form of temporary status.

Thousands went to Doral as Miami International Airport facilitated decades of growth.

Frank Carreño, president of the Venezuelan American Chamber of Commerce and a Doral resident for 18 years, said there is an air of uncertainty.

“What is going to happen? People don't want to return or can't return to Venezuela,” he said.

A woman and child walk down a commercial street, in Doral, Fla., Saturday, April 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Yrene Bruno works inside her franchise of "Sabor Venezolano," selling Venezuelan food and treats, in Doral, Fla., Tuesday, April 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

People walk along a street lined with restaurants and businesses in Doral, Fla., Saturday, April 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Residential neighborhoods are seen in Doral, Fla., Saturday, April 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Alvaro Duran Stella, 47, a Venezuelan with Temporary Protected Status (TPS) who studied to become a paralegal and now works in Doral, Fla., on immigration application cases for other migrants, walks back to his apartment after working remotely in his community's clubhouse, Saturday, April 5, 2025, in Miramar, Fla. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Venezuelan stickers and specialty products are sold alongside more typical offerings in a gas station shop in Doral, Fla., Tuesday, April 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

People walk down a commercial street in Doral, Fla., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

People shop in the Sabores Market, specializing in Venezuelan food and goods, Tuesday, April 1, 2025, in Doral, Fla. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Reinaldo Schanz, a 19-year-old U.S. citizen who emmigrated from Venezuela at age 2, practices moves on his rollerblades after finishing work as a park service aide in Doral Central Park, Wednesday, April 2, 2025, in Doral, Fla. Schanz said his family supports the administration going after migrants with criminal records, but was surprised to see people on Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and similar programs targeted as well. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

People wear virtual reality headsets as they immerse themselves in "Teleport to Venezuela," a 35-minute VR documentary by Noa Iimura exploring life in Venezuela, as the film's national and European tour kicks off in the largest Venezuelan community in the U.S., in Doral, Fla., Saturday, April 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

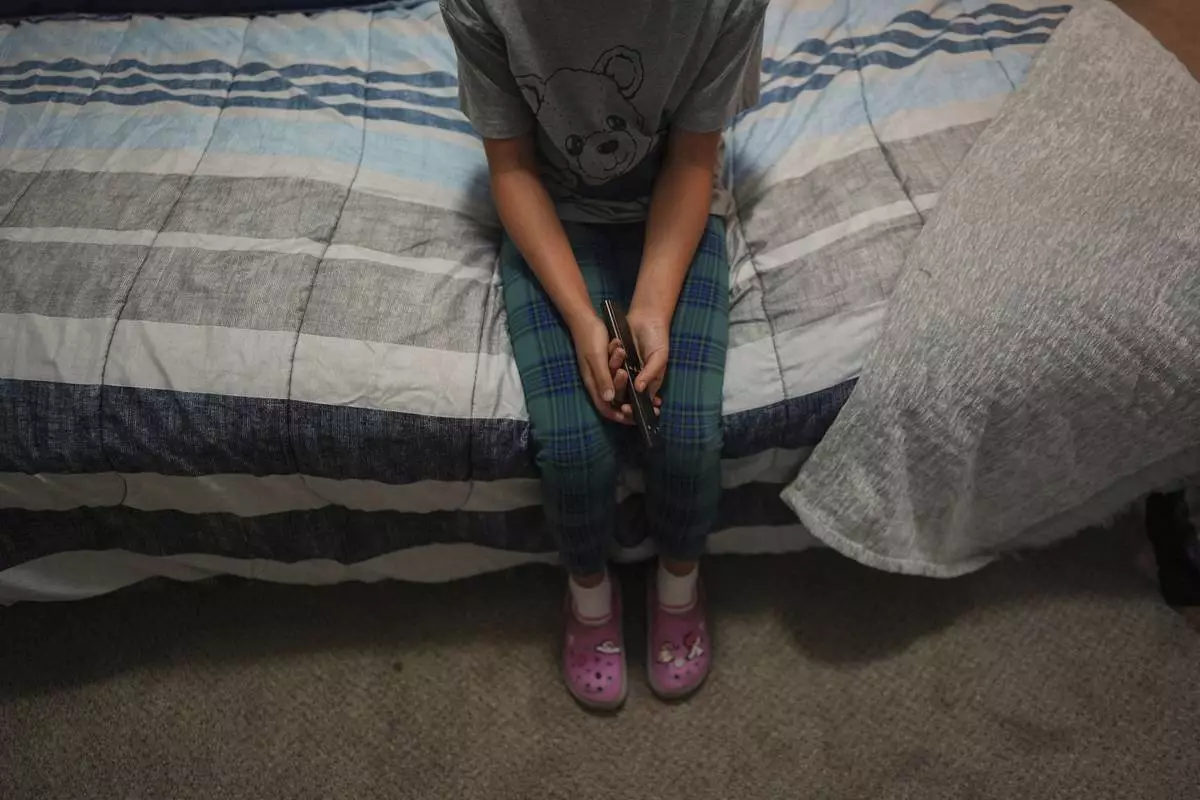

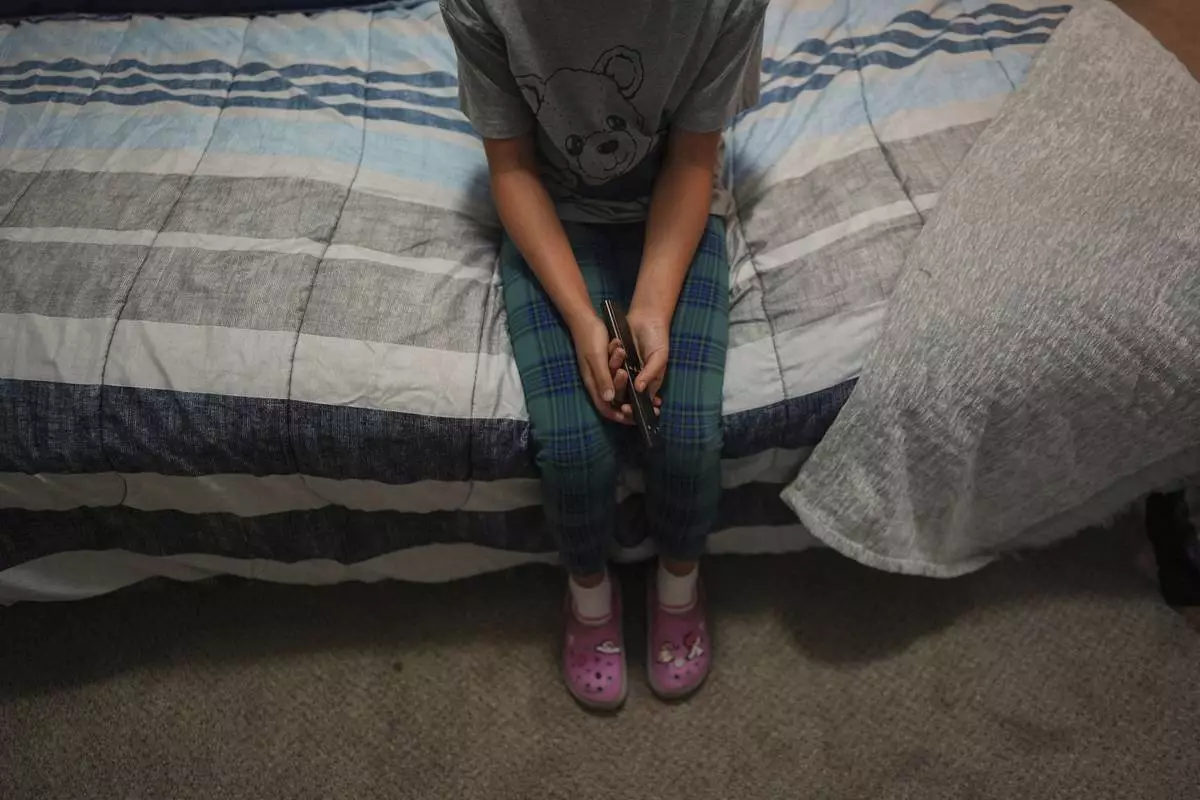

A 9-year-old girl with Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, who was born in Venezuela, but who fluently speaks only English and is in the gifted program at her school, watches TV in her family's apartment, Saturday, April 5, 2025, in Doral, Fla. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

A 9-year-old girl with Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, who was born in Venezuela, but who fluently speaks only English and is in the gifted program at her school, watches TV in her family's apartment, Saturday, April 5, 2025, in Doral, Fla. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Maria, a Venezuelan immigrant who lives with her U.S. citizen husband and two daughters who have Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, vacuums a rug as the family organizes and packs for their upcoming move into a larger and nicer apartment, Saturday, April 5, 2025, in Doral, Fla. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Gabriela Osuna, right, a 23-year-old Venezuelan immigrant with Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, who co-founded a successful artists collective that produces art events, takes a selfie with her girlfriend Vanessa Sanchez Montero, 29, also originally from Venezuela, at a bar in Doral, Fla., Saturday, April 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Cars pass through the area known as Downtown Doral, Saturday, April 5, 2025, in Doral, Fla. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Patrons eat inside one of the locations of Sabor Venezolano owned by Wilmer Escaray, who operates a dozen businesses that hire Venezuelan migrants like he once was, in Doral, Fla., Tuesday, April 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

![U.S. citizens who immigrated from Venezuela between 16 and 30 years ago play dominos outside El Arepazo, a restaurant that is a hub of the largest Venezuelan community in the U.S., in Doral, Fla., Wednesday, April 2, 2025. Many of the friends, including Cesar Mena, at right, voted for President Donald Trump and continue to support him. "I have family and friends on TPS [Temporary Protected Status] and I feel bad for them. But it's a temporary situation, and you need to resolve the problem." (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)](https://image.bastillepost.com/1200x/wp-content/uploads/global/2025/04/c69423facf44b6b804e1e5ae7a5cc99f_Immigration_Temporary_Status_Venezuelans_79573.jpg.webp)

U.S. citizens who immigrated from Venezuela between 16 and 30 years ago play dominos outside El Arepazo, a restaurant that is a hub of the largest Venezuelan community in the U.S., in Doral, Fla., Wednesday, April 2, 2025. Many of the friends, including Cesar Mena, at right, voted for President Donald Trump and continue to support him. "I have family and friends on TPS [Temporary Protected Status] and I feel bad for them. But it's a temporary situation, and you need to resolve the problem." (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

![U.S. citizens who immigrated from Venezuela between 16 and 30 years ago play dominos outside El Arepazo, a restaurant that is a hub of the largest Venezuelan community in the U.S., in Doral, Fla., Wednesday, April 2, 2025. Many of the friends, including Cesar Mena, at right, voted for President Donald Trump and continue to support him. "I have family and friends on TPS [Temporary Protected Status] and I feel bad for them. But it's a temporary situation, and you need to resolve the problem." (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)](https://image.bastillepost.com/1200x/wp-content/uploads/global/2025/04/c69423facf44b6b804e1e5ae7a5cc99f_Immigration_Temporary_Status_Venezuelans_79573.jpg.webp)