Lucía Giménez still suffers pain in her knees from the years she spent scrubbing floors in the men’s bathroom at the Opus Dei residence in Argentina’s capital for hours without pay.

Giménez, now 56, joined the conservative Catholic group in her native Paraguay at the age of 14 with the promise she would get an education. But instead of math or history, she was trained in cooking, cleaning and other household chores to serve in Opus Dei residences and retirement homes.

For 18 years she washed clothes, scrubbed bathrooms and attended to the group’s needs for 12 hours a day, with breaks only for meals and praying. Despite her hard labor, she says: “I never saw money in my hands.”

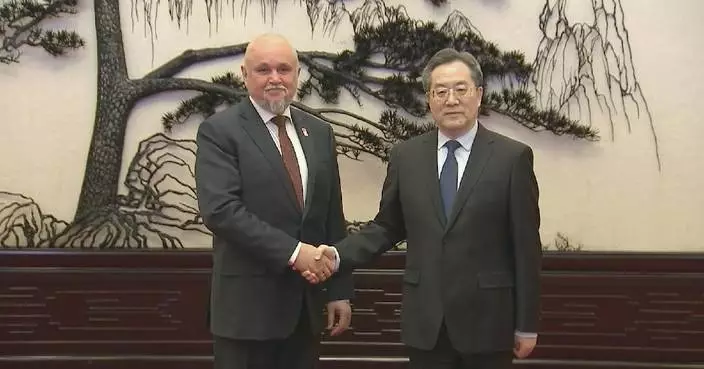

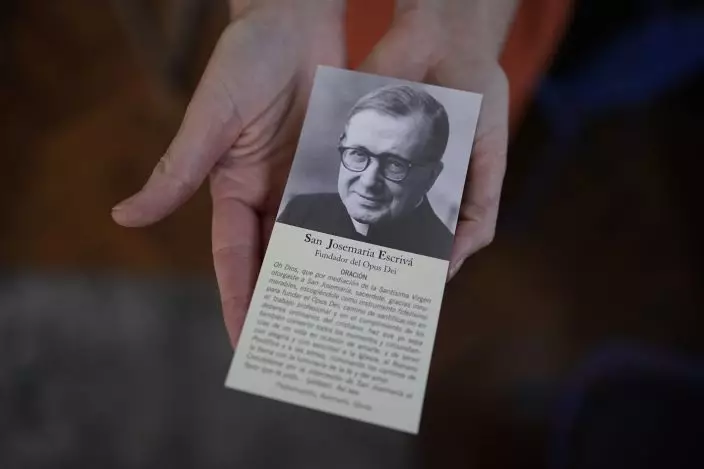

Josefina Madariaga, director of Opus Dei’s press office in Argentina, holds a photo of Opus Dei founder Josemaria Escriva de Balaguer, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Thursday, Nov. 4, 2021. Opus Dei (Work of God in Latin) was founded by the Spanish priest in 1928. (AP PhotoVictor R. Caivano)

Giménez and 41 other women have filed a complaint against Opus Dei to the Vatican for alleged labor exploitation, as well as abuse of power and of conscience. The Argentine and Paraguayan citizens worked for the movement in Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, Uruguay, Italy and Kazakhstan between 1974 and 2015.

Opus Dei — Work of God in Latin — was founded by the Spanish priest Josemaría Escrivá in 1928, and has 90,000 members in 70 countries. The lay group, which was greatly favored by St. John Paul II, who canonized Escrivá in 2002, has a unique status in the church and reports directly to the pope. Most members are laymen and women with secular jobs and families who strive to “sanctify ordinary life.” Other members are priests or celibate lay people.

The complaint alleges the women, often minors at the time, labored under “manifestly illegal conditions" that included working without pay for 12 hours-plus without breaks except for food or prayer, no registration in the Social Security system and other violations of basic rights.

Lucia Gimenez, who worked for Opus Dei for 18 years as a numerary assistant, poses for a photo in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Thursday, Oct. 21, 2021. Giménez, now 56, says she joined the conservative Catholic group in her native Paraguay at the age of 14 with the promise that she would receive a higher education. But instead of math or history, she was trained in cooking, cleaning and other household chores to serve in Opus Dei centers, residences and retirement homes. (AP PhotoNatacha Pisarenko)

The women are demanding financial reparations from Opus Dei and that it acknowledges the abuses and apologizes to them, as well as the punishment of those responsible.

“I was sick of the pain in my knees, of getting down on my knees to do the showers,” Giménez told The Associated Press. “They don’t give you time to think, to criticize and say that you don’t like it. You have to endure because you have to surrender totally to God.”

In a statement to the AP, Opus Dei said it had not been notified of the complaint to the Vatican but has been in contact with the women's legal representatives to “listen to the problems and find a solution.”

Beatriz Delgado, who worked as a numerary assistant for 23 years in Argentina and Uruguay, poses for a photo in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Thursday, Oct. 21, 2021. Delgado who began working for Opus Dei at the age of 18, said they told her “that I had to give my salary to the director and that everyone gave it ... it was part of giving to God.” (AP PhotoNatacha Pisarenko)

The women in the complaint have one thing in common: humble origins. They were recruited and separated from their families between the ages of 12 and 16. In some cases, like Gimenez's, they were taken to Opus Dei centers in another country, circumventing immigration controls.

They claim that Opus Dei priests and other members exercised “coercion of conscience” on the women to pressure them to serve and to frighten them with spiritual evils if they didn't comply with the supposed will of God. They also controlled their relations with the outside world.

Most of the women asked to leave as the physical and psychological demands became intolerable. But when they finally did, they were left without money. Many also said they needed psychological treatment after leaving Opus Dei.

Beatriz Delgado holds an undated photo of herself working in the kitchen of an Opus Dei house, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Thursday, Nov. 4, 2021. After spending seven years in an Opus Dei center in Uruguay, Delgado “escaped” and boarded a ship bound for Buenos Aires. There, a numerary was waiting for her. (AP PhotoVictor R. Caivano)

“The hierarchy (of Opus Dei) is aware of these practices,” said Sebastián Sal, the women's lawyer. “It is an internal policy of Opus Dei. The search for these women is conducted the same way throughout the world. ... It is something institutional.”

The women's complaint, filed in September with the Vatican Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, also points to dozens of priests affiliated with Opus Dei for their alleged “intervention, participation and knowledge in the denounced events.”

The allegations in the complaint are similar to those made by members of another conservative Catholic organization also favored by St. John Paul II, the Legion of Christ. The Legion recruited young women to become consecrated members of its lay branch, Regnum Christi, to work in Legion-run schools and other projects.

Alicia Torancio, who began working for Opus Dei at the age of 16, poses for a photo in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Thursday, Oct. 21, 2021. Torancio is one of 41 women who have filed a complaint against Opus Dei to the Vatican for alleged labor exploitation, and abuses of power and of conscience. (AP PhotoNatacha Pisarenko)

Those women alleged spiritual and psychological abuse, of being separated from family and being told their discomfort was “God’s will” and that abandoning their vocation would be tantamount to abandoning God.

Pope Francis has been cracking down on 20th-century religious movements after several religious orders and lay groups were accused of sexual and other abuses by their leaders. Opus Dei has so far avoided much of the recent controversy, though there have been cases of individual priests accused of misconduct.

“We do not have any official notification from the Vatican about the existence of a complaint of this type,” Josefina Madariaga, director of Opus Dei’s press office in Argentina, told the AP. She said the women's lawyer informed the group last year of their complaints about the lack of contributions to Argentina's social security system.

“If there is a traumatic experience or one that has left them with a wound, we want to honestly listen to them, understand what happened and from there correct what has to be corrected,” she said.

She added that all the people currently “working on site are paid,” adding that some 80 women currently work for Opus Dei in Argentina.

However, she said, “in the 60′s, 70′s, 80′s, 90′s, society as a whole dealt with these issues in a more informal or family way. ... Opus Dei has made the necessary changes and modifications to accompany the law in force today.”

Beatriz Delgado, who worked for Opus Dei for 23 years in Argentina and Uruguay, said she was told “that I had to give my salary to the director and that everyone gave it. ... It was part of giving to God.”

“They convince you with the vocation, with ‘God calls you, God asks this of you, you cannot fail God.’ ... They hooked me with that,” she said.

So far, the Vatican has not ruled on the complaint and it’s not clear if it will. A Vatican spokesperson did not immediately respond to a request for information.

If there is no response, the women's legal representatives say they will initiate criminal proceedings for “human trafficking, reduction to servitude, awareness control and illegitimate deprivation of liberty” against Opus Dei in Argentina and other countries the women worked in.

Argentine law sanctions human trafficking with prison sentences of four to 15 years. The statute of limitations is 12 years after the alleged crime ceases.

“They say, ‘we are going to help poor people,’ but it’s a lie; they don’t help, they keep (the money) for themselves,” Giménez said. “It is very important to achieve some justice.”