MANILA, Philippines (AP) — A Filipino villager has been nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea.

On Friday, over a hundred people watched on as 10 devotees were nailed to wooden crosses, among them Ruben Enaje, a 63-year-old carpenter and sign painter. The real-life crucifixions have become an annual religious spectacle that draws tourists in three rural communities in Pampanga province, north of Manila.

Click to Gallery

Filipino flagellants participate in Good Friday rituals to atone for their sins, in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Ruben Enaje is lowered from the cross during the reenactment of Jesus Christ's sufferings as part of Good Friday rituals in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. The Filipino villager was nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Ruben Enaje grimaces as a nail was removed from one of his hands during the reenactment of Jesus Christ's sufferings as part of Good Friday rituals in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. The Filipino villager was nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Ruben Enaje remains on the cross during a reenactment of Jesus Christ's sufferings as part of Good Friday rituals in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. The Filipino villager was nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Ruben Enaje grimaces from being nailed to the cross during the reenactment of Jesus Christ's sufferings as part of Good Friday rituals in the San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. The Filipino villager was nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Filipino penitents carry their crosses atop the crucifixion mound during Good Friday rituals in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Filipino flagellants walk along San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024, to atone for their sins during Good Friday rituals. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Ruben Enaje, center, remains on the cross flanked by two other devotees during a reenactment of Jesus Christ's sufferings as part of Good Friday rituals in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. The Filipino villager was nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Ruben Enaje remains on the cross during the reenactment of Jesus Christ's sufferings as part of Good Friday rituals in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. The Filipino villager was nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

A hooded Filipino penitent flagellates himself as part of Holy Week rituals to atone for sins or fulfill vows for an answered prayer in metropolitan Manila, Philippines on Maundy Thursday, March 28, 2024. The bizarre lenten ritual is frowned upon by the church in this predominantly Roman Catholic country. (AP Photo/Aaron Favila)

A hooded Filipino penitent carries pointed bamboo sticks as part of Holy Week rituals to atone for sins or fulfill vows for an answered prayer in metropolitan Manila, Philippines on Maundy Thursday, March 28, 2024. The bizarre lenten ritual is frowned upon by the church in this predominantly Roman Catholic country. (AP Photo/Aaron Favila)

FILE - Shadows of protesters carrying wooden crosses are reflected on the street as they reenact the sufferings of Jesus Christ during a rally on holy week in Manila, Philippines, on March 27, 2018. A Filipino villager plans to be nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Aaron Favila, File)

The gory ritual resumed last year after a three-year pause due to the coronavirus pandemic. It has turned Enaje into a village celebrity for his role as the “Christ” in the Lenten reenactment of the Way of the Cross.

Ahead of the crucifixions, Enaje told The Associated Press by telephone Thursday night that he has considered ending his annual religious penitence due to his age, but said he could not turn down requests from villagers for him to pray for sick relatives and all other kinds of maladies.

The need for prayers has also deepened in an alarming period of wars and conflicts worldwide, he said.

"If these wars worsen and spread, more people, especially the young and old, would be affected. These are innocent people who have totally nothing to do with these wars,” Enaje said.

Despite the distance, the wars in Ukraine and Gaza have helped send prices of oil, gas and food soaring elsewhere, including in the Philippines, making it harder for poor people to stretch their meagre income, he said.

Closer to home, the escalating territorial dispute between China and the Philippines in the South China Sea has also sparked worries because it’s obviously a lopsided conflict, Enaje said. “China has many big ships. Can you imagine what they could do?" he asked.

"This is why I always pray for peace in the world,” he said and added he would also seek relief for people in southern Philippine provinces, which have been hit recently by flooding and earthquakes.

In the 1980s, Enaje survived nearly unscathed when he accidentally fell from a three-story building, prompting him to undergo the crucifixion as thanksgiving for what he considered a miracle. He extended the ritual after loved ones recovered from serious illnesses, one after another, and he landed more carpentry and sign-painting job contracts.

“Because my body is getting weaker, I can’t tell … if there will be a next one or if this is really the final time,” Enaje said.

During the annual crucifixions on a dusty hill in Enaje’s village of San Pedro Cutud in Pampanga and two other nearby communities, he and other religious devotees, wearing thorny crowns of twigs, carried heavy wooden crosses on their backs for more than a kilometer (more than half a mile) under a hot summer sun. Village actors dressed as Roman centurions hammered 4-inch (10-centimeter) stainless steel nails through their palms and feet, then set them aloft on wooden crosses for about 10 minutes as dark clouds rolled in and a large crowd prayed and snapped pictures.

Among the crowd this year was Maciej Kruszewski, a tourist from Poland and a first-time audience member of the crucifixions.

“Here, we would like to just grasp what does it mean, Easter in completely different part of the world,” said Kruszewski.

Other penitents walked barefoot through village streets and beat their bare backs with sharp bamboo sticks and pieces of wood. Some participants in the past opened cuts in the penitents’ backs using broken glass to ensure the ritual was sufficiently bloody.

Many of the mostly impoverished penitents undergo the ritual to atone for their sins, pray for the sick or for a better life, and give thanks for miracles.

The gruesome spectacle reflects the Philippines’ unique brand of Catholicism, which merges church traditions with folk superstitions.

Church leaders in the Philippines, the largest Catholic nation in Asia, have frowned on the crucifixions and self-flagellations. Filipinos can show their faith and religious devotion, they say, without hurting themselves and by doing charity work instead, such as donating blood, but the tradition has lasted for decades.

Filipino flagellants participate in Good Friday rituals to atone for their sins, in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Ruben Enaje is lowered from the cross during the reenactment of Jesus Christ's sufferings as part of Good Friday rituals in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. The Filipino villager was nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Ruben Enaje grimaces as a nail was removed from one of his hands during the reenactment of Jesus Christ's sufferings as part of Good Friday rituals in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. The Filipino villager was nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Ruben Enaje remains on the cross during a reenactment of Jesus Christ's sufferings as part of Good Friday rituals in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. The Filipino villager was nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Ruben Enaje grimaces from being nailed to the cross during the reenactment of Jesus Christ's sufferings as part of Good Friday rituals in the San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. The Filipino villager was nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Filipino penitents carry their crosses atop the crucifixion mound during Good Friday rituals in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Filipino flagellants walk along San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024, to atone for their sins during Good Friday rituals. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Ruben Enaje, center, remains on the cross flanked by two other devotees during a reenactment of Jesus Christ's sufferings as part of Good Friday rituals in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. The Filipino villager was nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

Ruben Enaje remains on the cross during the reenactment of Jesus Christ's sufferings as part of Good Friday rituals in San Pedro Cutud, north of Manila, Philippines, Friday, March 29, 2024. The Filipino villager was nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Gerard V. Carreon)

A hooded Filipino penitent flagellates himself as part of Holy Week rituals to atone for sins or fulfill vows for an answered prayer in metropolitan Manila, Philippines on Maundy Thursday, March 28, 2024. The bizarre lenten ritual is frowned upon by the church in this predominantly Roman Catholic country. (AP Photo/Aaron Favila)

A hooded Filipino penitent carries pointed bamboo sticks as part of Holy Week rituals to atone for sins or fulfill vows for an answered prayer in metropolitan Manila, Philippines on Maundy Thursday, March 28, 2024. The bizarre lenten ritual is frowned upon by the church in this predominantly Roman Catholic country. (AP Photo/Aaron Favila)

FILE - Shadows of protesters carrying wooden crosses are reflected on the street as they reenact the sufferings of Jesus Christ during a rally on holy week in Manila, Philippines, on March 27, 2018. A Filipino villager plans to be nailed to a wooden cross for the 35th time to reenact Jesus Christ’s suffering in a brutal Good Friday tradition he said he would devote to pray for peace in Ukraine, Gaza and the disputed South China Sea. (AP Photo/Aaron Favila, File)

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina (AP) — Jorge Mario Bergoglio, born in Buenos Aires, never set foot in his homeland after becoming Pope Francis in 2013.

That left many of the faithful in Argentina feeling puzzled and snubbed by the world’s first Latin American pope. The question of why he never returned quickly dominated airwaves and headlines on Tuesday in Buenos Aires.

Francis, who died Monday, said little about his decision to steer clear of Argentina. But Vatican insiders and interlocutors said the pontiff wanted to avoid getting swept up in the polarizing politics that characterized his country.

“It’s sad, because we should have been proud to have an Argentine pope,” said Ardina Aragon, 94, a longtime friend and neighbor from the middle-class neighborhood of Flores where Francis was born in 1936. “I think there were political factors that influenced him.”

Francis, a devotee of soccer, tango and other signature aspects of Argentine culture, was known to have tense relationships with some of his country’s leaders. His ideological clash with President Javier Milei, who took office in 2023, created even more challenges.

Argentina celebrated Francis’ becoming pope with an ecstasy otherwise reserved for the country's three World Cup soccer championships. But that initial excitement over the former archbishop of Buenos Aires faded as the years passed.

A recent Pew Research Center report showed that Francis’ popularity had dropped more in Argentina than anywhere else in the region over the last decade. About 64% of respondents said they had a positive view of Francis in September 2024, compared with 91% in 2014.

“There are many among us who think he made mistakes. Not everyone in our community is proud of the association,” said Adriana Lombardi, 62, a retired teacher in Buenos Aires, referring to traditionalist Catholics in Argentina and beyond who accused Francis of leading the church astray.

Some in Buenos Aires felt slighted by Francis' avoidance of Argentina.

“Despite his history here, it seems like he doesn't care about us," said Bruno Rentería, 19, who was praying in front of an icon of the Virgin Mary at the Basílica de San José de Flores in Buenos Aires. Older churchgoers recalled the very confessional where Bergoglio, at age 16, had first heard the call to the priesthood. “It's odd because it seems like he has time for everyone else.”

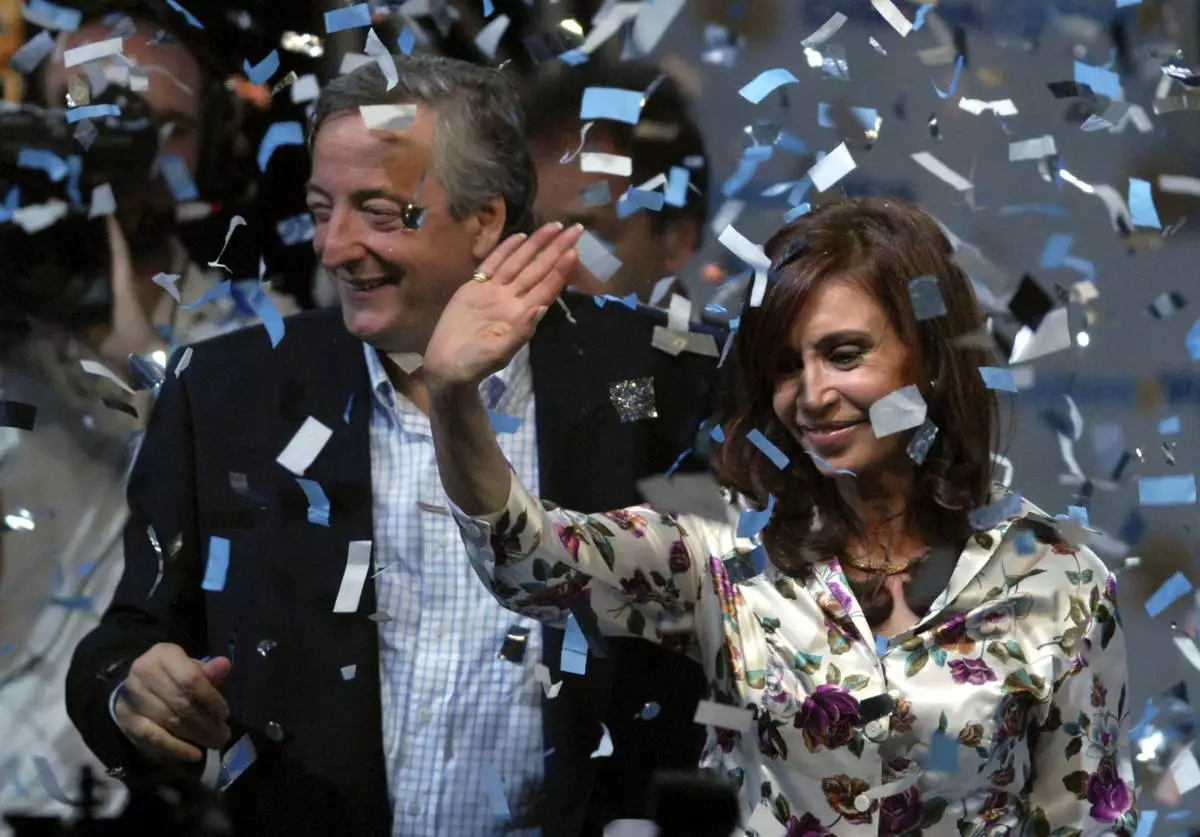

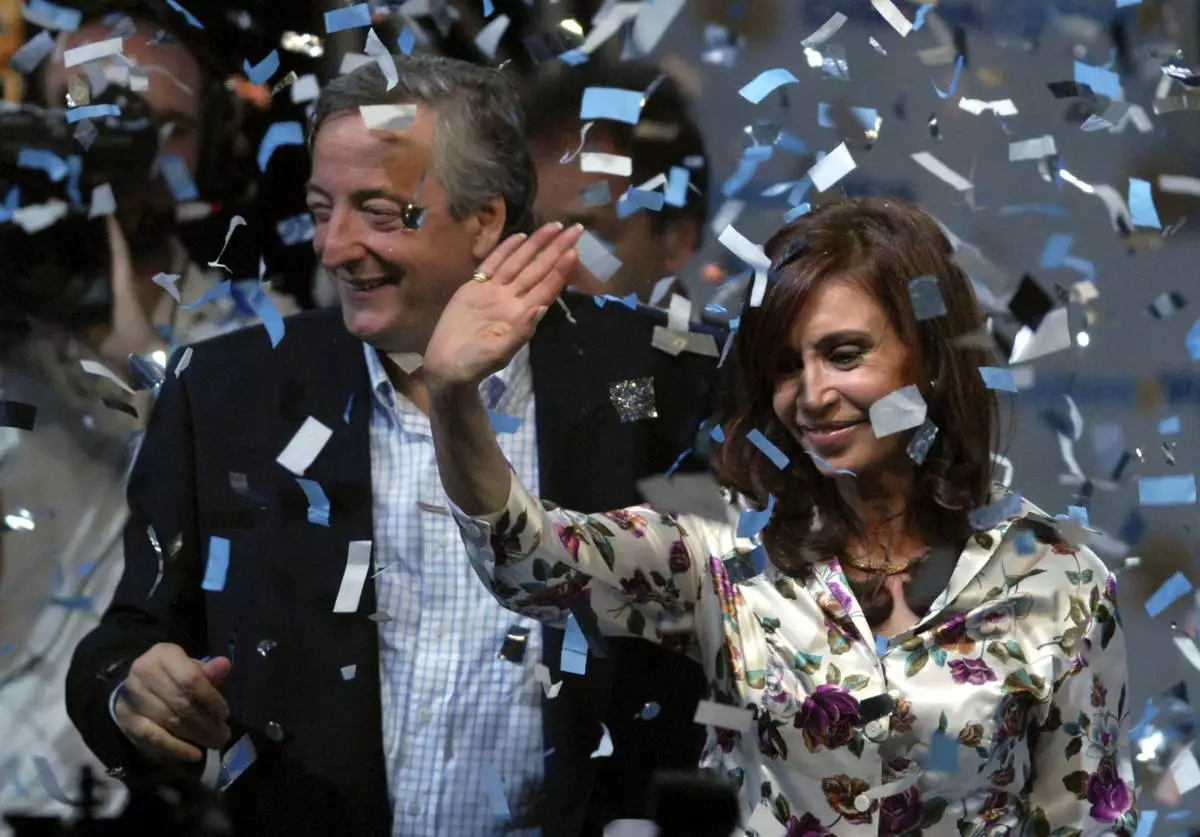

Some trace those tensions to when he was archbishop of Buenos Aires during the leftist tenures of the late former President Néstor Kirchner and his successor and wife, the divisive Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, whose strain of populism dominated Argentine politics for decades.

Francis and Fernández de Kirchner were unfriendly neighbors in Plaza de Mayo, the central square that hosts both the government headquarters and the cathedral where Francis delivered homilies during much of her presidency from 2007-15.

From the pulpit, Francis criticized the “exhibitionism” and autocratic tendencies of Argentina’s political class — a subtle dig that the Kirchners interpreted as a direct attack. His support for the Vatican’s conservative positions on key social issues deepened rifts with Fernández de Kirchner’s progressive government as it expanded sex education and, in 2010, legalized same-sex marriage — a first for Latin America.

Perhaps most significantly, supporters of the Kirchners accused Francis of complicity in Argentina’s 1976-83 military dictatorship, when as many as 30,000 people were estimated by human rights groups to have been killed or simply “disappeared.” Francis was head of Argentina’s Jesuit order during those violent years, when the junta targeted radical clerics and priests who worked with the poor.

Francis rejected the accusations of complicity. In his 2024 memoir, “Life: My Story Through History,” he recalled hiding wanted activists and pressing military officials behind the scenes to free two abducted priests from his order.

Eventually, Kirchner's social welfare policies resonated with Bergoglio. The two drew closer after he became pontiff and set about softening the image of an institution that had long appeared forbidding.

"Conservatives in Argentina failed to understand his change of attitude," said Sergio Berensztein, who runs a political consultancy in Buenos Aires.

Unsettled by his critiques of the excesses of capitalism, right-wing critics branded Francis the “Peronist pope” — a reference to the Argentine populist movement founded by three-time President Juan Domingo Perón, who employed an authoritarian hand and powerful state to champion social justice causes.

From that point on, Berensztein said, Francis “felt everything he said or did would lead to fighting on either side of the divide.”

Francis' politics came under more scrutiny in 2016, when he wore an unusually grim expression while posing for a photo beside former President Mauricio Macri, Kirchner’s conservative successor, whose austerity program battered the poor.

The awkward photo op paled in comparison to Francis’ discomfort with what followed.

Milei, a former television pundit and corporate economist, called Francis an “imbecile” and “the representative of the Evil One on Earth" before coming to power in 2023. He lashed out at the pope for promoting social justice, supporting taxes and sympathizing with “murderous communists.”

Francis expressed sympathy for the strife of Argentines pulled into poverty as they bore the brunt of Milei’s fiscal shock therapy, voicing concern over what he called a “save yourself approach” to doing politics and publicly criticizing Argentine security forces for using pepper spray against Argentine retirees protesting for better pensions.

The Vatican described a meeting between Francis and Milei in 2024 as “cordial,” but ideological differences resurfaced with the ascension of Milei’s political ally, U.S. President Donald Trump.

Since Trump's reelection, Francis has intensified direct attacks on the administration, criticizing its mass deportation of migrants and other policies.

“Francis cultivated a social doctrine in the church that generated opposition, particularly among conservatives in the United States,” said Sergio Rubin, an Argentine journalist and Francis' authorized biographer.

After a dozen years of papal travel — including to nearly all Argentina’s neighbors — Francis referenced a plan to visit his native land last year. Nothing came of it.

“He went to Brazil, Peru, Chile; he passed over our heads,” said Lucia Vidal, a retired nurse who attended Bergoglio’s Mass when he was archbishop. “That pains me."

In contrast, Pope John Paul II visited his native Poland less than a year after becoming pontiff in 1978. His successor, Pope Benedict XVI, chose his native Germany for his first foreign trip in 2005.

Other Argentines seemed less indignant about the snub and more grateful for his contributions to the impoverished neighborhoods of Buenos Aires, where Bergoglio first earned fame as the “slum bishop," leading processions, creating a cadre of priests who follow in his footsteps and founding shelters for homeless addicts and community centers on violence-scarred streets.

“I can’t express what his humility, his open hands, meant to me, my family, my neighborhood,” said Angela Cano, 51, at a Mass held in his honor Monday at Villa 21-24, a neglected suburb near the railroad. "We saw up close how he was the pope of the people. He helped us find God.”

Back in Flores, Carlos Liva, 66, a retired cab driver, said that he couldn't begrudge the pope for prioritizing the rest of the world after spending most of his years in Argentina.

“It's clear that he felt at ease in Rome,” Liva said. ”In his own country, people found every reason to question him."

Natacha Pisarenko contributed to this report.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

The Cathedral, left, stands in Buenos Aires' main square, Argentina, following the Vatican's announcement of Pope Francis' death, Monday, April 21, 2025. (AP Photo/Victor R. Caivano)

Maria Teresa Delgado holds a portrait of the late Pope Francis during Mass at the Basílica de San José de Flores, where he worshipped as a youth, following the Vatican's announcement of his death in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Monday, April 21, 2025. (AP Photo/Gustavo Garello)

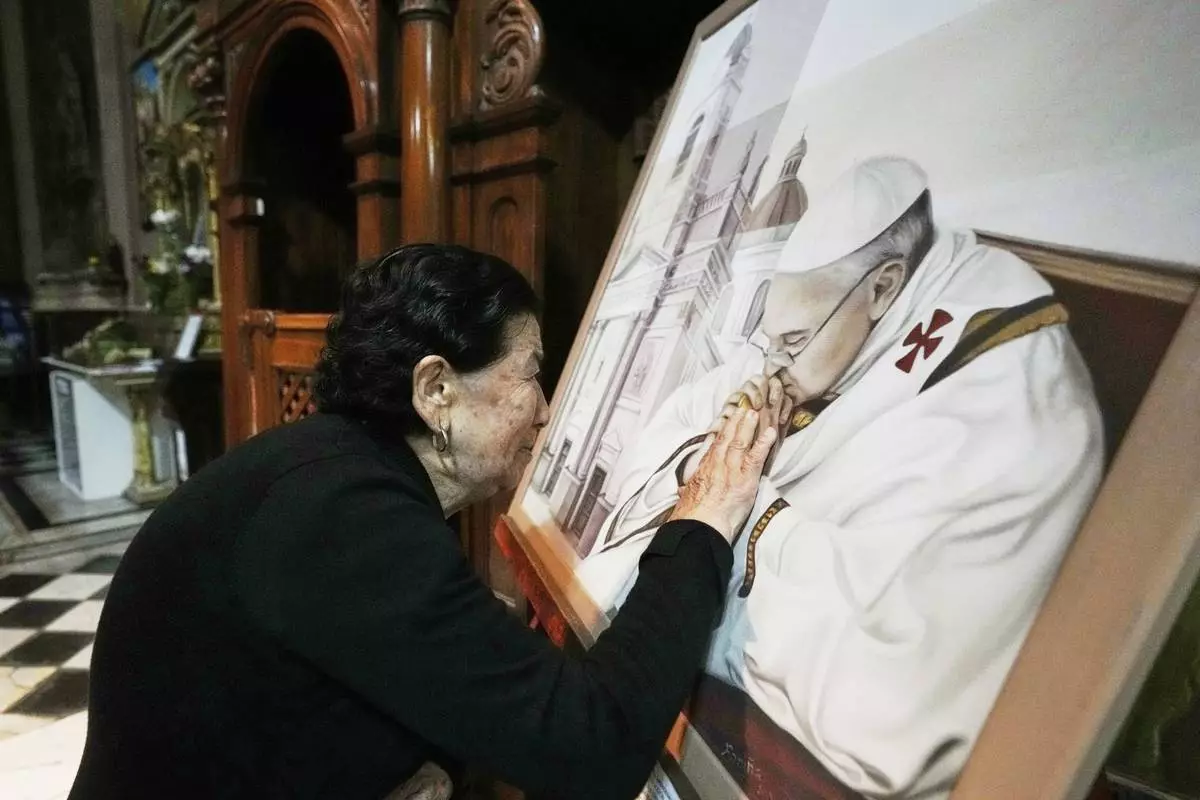

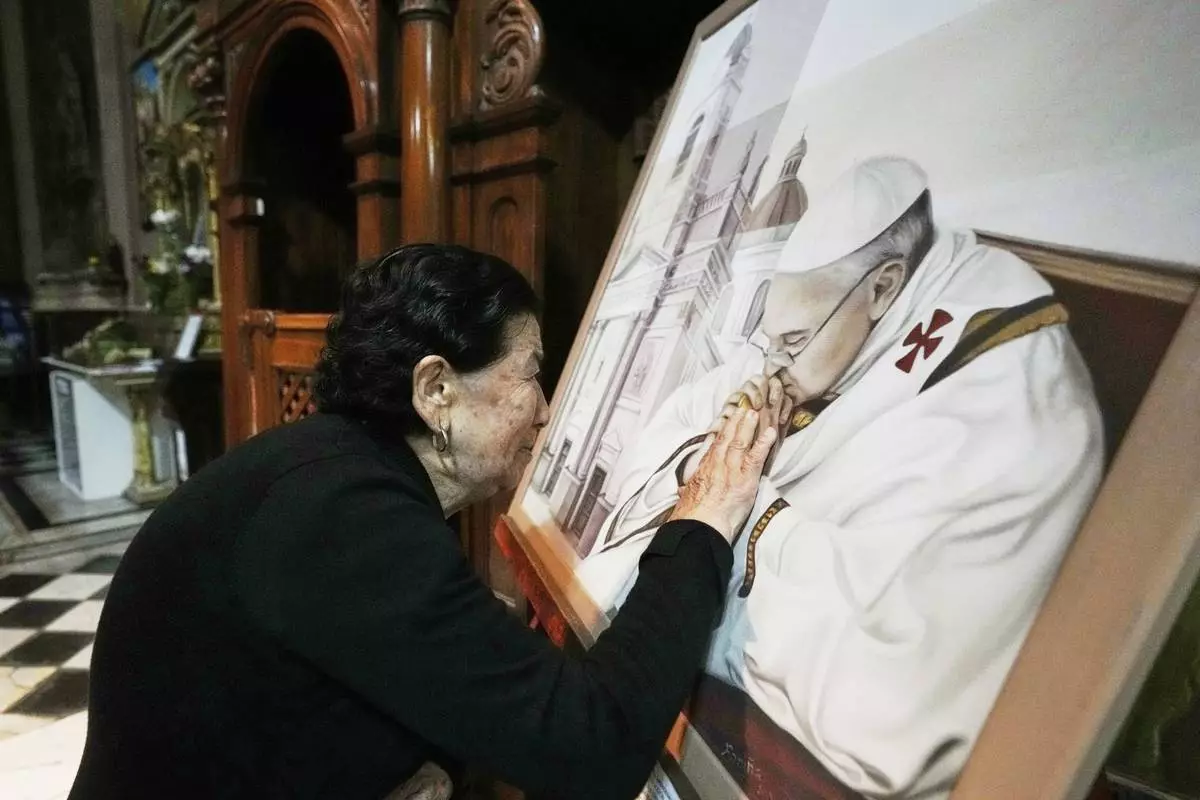

Genali Nogales touches a painting of the late Pope Francis at the Basílica de San José de Flores, where he worshipped as a youth, following the Vatican's announcement of his death in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Monday, April 21, 2025. (AP Photo/Gustavo Garello)

FILE - Argentina's President Javier Milei speaks at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center, Feb. 22, 2025, in Oxon Hill, Md. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana, File)

FILE - Pope Francis waves during the Angelus noon prayer delivered from his studio window overlooking St. Peter's Square, at the Vatican, Oct. 4, 2020. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)

FILE - Argentine presidential candidate Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, right, and Argentina's President Nestor Kirchner wave to supporters at their headquarters in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Oct. 28, 2007. (AP Photo/Daniel Luna, File)

FILE - A man rides a bicycle near a weathered mural of Pope Francis in Buenos Aires, Argentina, March 2, 2023. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko, File)

FILE - Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, second from left, travels on the subway in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 2008. (AP Photo/Pablo Leguizamon, File)

FILE - In this Aug. 7, 2009 file photo, Argentina's Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio gives a Mass outside the San Cayetano church where an Argentine flag hangs behind in Buenos Aires, Argentina. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko, file)